If You Don't Prioritize Your Life, Someone Else Will.

If you don’t prioritize your life, someone else will.

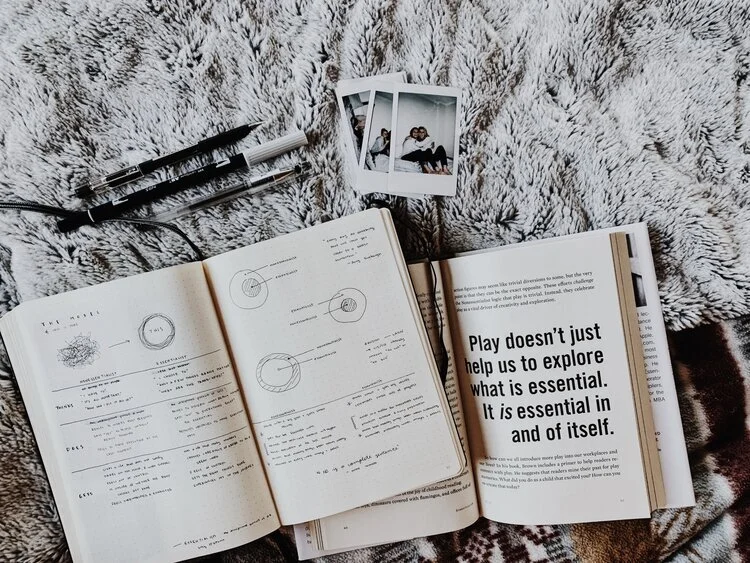

Essentialism, The Disciplined Pursuit of Less

Some books are worth reading once, then twice, and even more. I have a re-read list, fiction and non-fiction. The non-fiction books are filled with truths that keep me on the path toward my big Why and provide skills I need to keep learning and practicing. These books are also dense with insights and each time I read them I learn more.

Essentialism, The Disciplined Pursuit of Less by Greg McKeown is a great re-read choice for the new year. McKeown begins with a story of leaving his wife and hours-old baby in the hospital to go to a business meeting. Exactly nothing came from the client meeting, but it took him from what was most important, and taught him this crucial lesson: If you don’t prioritize your life, someone else will.

As I’ve left the world of deadlines, back-to-back meetings and long work weeks, you would think that the pressure of time management would be gone. Surprisingly, it’s the opposite. External stress has been replaced with an increased personal accountability of being sure I spend my time on what matters most – what is essential.

Essentialism, as defined by McKeown, is constantly pausing to ask, “Am I investing in the right activities?” The right activities are those vital few that inspire us, maximize our skills and talents, and focus our energies on how we can best contribute to the world.

Once we identify our vital few, we then have to create a system or method by which we make daily decisions about whether to say yes or politely decline. “It’s a method for making the tough trade-off between lots of good things and a few really great things. It’s about learning how to do less but better so you can achieve the highest possible return on every precious moment of your life.”

The book clarifies the differences between an essentialist and a nonessentialist and the contrast is persuasive. The nonessentialist believes they must be all things to all people, tries to do everything, and consequently, lives a stressed life that feels out of control. The essentialist believes less is better, routinely pauses before saying “yes”, and feels in control of her time and her choices.

Each time I read this book I see how easily I get sucked into the nonessential vortex. There are so many choices, so many attention-grabbing noises, and being busy appears as social evidence of importance. When asked, “what have you been doing?” I feel an anxiety rush to provide a list of busy activities with no discernment whatsoever as to their real value.

How to become an essentialist is well-outlined in the chapters with specific ideas on eliminating the “trivial many” and creating a system where essentialism becomes the easy choice. Through compelling stories and examples, McKeown paints a clear picture of why I want to live an essentialist life and the steps required to move in that direction. If this topic interests you, invest in reading this book.

A final question for you from the book:

“When we look back on our careers and our lives, would we rather see a long laundry list of ‘accomplishments’ that don’t really matter or just a few major accomplishments that have real meaning and significance?”